Northern Lights

Runes lie at the heart of the Blood of Woden adventure series. They were the only form of writing known to the pagan Norse and heathen English in the Dark Ages.

Northern Lights

Runes lie at the heart of the Blood of Woden adventure series. They were the only form of writing known to the pagan Norse and heathen English in the Dark Ages.

Two thousand years ago, strange new shapes began to appear in the woods and marshes of Northern Europe. What were they and where did they come from?

Runes are one of the better-known parts of our heathen heritage. With their scratched lines and jagged strokes, they fit perfectly with the violent image of the Saxons and Vikings: harsh tokens of a bloodthirsty age.

The truth is rather more practical. The nations who used the runes carved mostly in wood, so they avoided curves and horizontal lines, which go against the grain and are tricky to cut. This left an alphabet based on uprights and diagonals, giving the twiglike shapes we know today. When carved, the shapes of the runes are known as staves.

Most of what was carved has been lost, and much of what survives is crude and simple. There are, however, some objects which display the highest workmanship, in terms of both carving and wordsmithing. As so often with this period, we have just enough to construct a history, but not quite enough to put flesh on the bones.

The First Word

Runes formed the first English alphabet. The first words of English were thus written in runes.

The First Word

Runes formed the first English alphabet. The first words of English were thus written in runes.

Think what you're reading is the English alphabet? Think again.

The words you are reading are written in the Roman alphabet. This alphabet was not used to write English until the eighth century, and did not become its main form of writing until the ninth. Before this, English was written using runes.

So what are runes? Put simply, they are the letters which were used to write the various Germanic languages before these languages began using the Roman alphabet. The Germanic group includes English, Flemish, Dutch, German and most Scandinavian tongues (though notably not Finnish).

The earliest confirmed runic inscriptions date to the second century AD. They are believed to have been based on a northern Italian script, which explains why some bear a likeness to Roman letters. At the time of these first inscriptions, the Germanic tongues were spoken across a broad swathe of northern and central Europe, roughly from the Rhine to the Vistula and from the Danube up to central Scandinavia. These languages, and the nations who spoke them, were by then split into an eastern and a western group. Runes were never used much by the eastern group, whose speakers had mostly left their homelands and mingled with other cultures by the sixth century. In the west, however, they would remain in use for more than a thousand years.

The Germanic nations wrote very little in these early days, and few folk indeed would have known runes. The earliest complete alphabet dates to around 400 AD, and until the seventh century, runes were used only to write names, single words or brief statements. Prose, poetry and lawcodes were all learnt by ear.

The runes changed over time, both in shape and in sound. They also varied from place to place. The first runic alphabet, known as the Elder Futhark, was in use across the Germanic world from the second to the eighth centuries. It had twenty-four runes. The word 'futhark' comes from the first six runes in the sequence, which gave the sounds F, U Th, A, R and K. This word is a modern term and would not have been used at the time. From the sixth century, new versions of the Futhark began to appear, reflecting changes in speech around the Germanic world. The Elder Futhark continued to be used alongside them for a few generations, but eventually fell out of use.

In eastern Britain and along the Frisian coast, new runes were added to the Futhark, and the sounds of other runes were altered. Due to these changes, the Anglo-Frisian runes of the sixth century onward are known as the Futhorc, and it is these which feature in The Runemaster. A total of thirty-three runes have been recorded, although few inscriptions use all thirty-three. The coming of Christianity resulted in a burst of runic writing in Britain, including poetry and prose for the first time. Several fine runic objects are known from the eighth century, most notably the Franks Casket and Ruthwell Cross. As writing spread, however, so too did the Roman alphabet, and runes fell from favour in Britain. By the tenth century, they were used only as a novelty in poetry and riddles.

In Scandinavia, a shorter runic alphabet emerged in the eighth century, known as the Younger Futhark. It comprised only sixteen runes, meaning several runes had to cover more than one sound. This new futhark flourished during the Viking age, as Scandinavians came into contact with literate nations across Europe. Runestones became common, being raised as gravestones wherever the Vikings settled, but runes were also used to write law codes and private messages. Although their use declined after Christianisation in the twelfth century, they continued to be used in a few districts right into the modern era, by this time expanded to a set of twenty-seven staves.

The eighteenth century saw a rekindled interest in runes which has persisted to this day. Aside from the language itself, they are the best-preserved feature of pre-Christian English culture.

A Kind of Magic

Runic magic was an important part of pagan or heathen Germanic culture. It forms the backbone of the storyline in the Blood of Woden books.

A Kind of Magic

Runic magic was an important part of pagan or heathen Germanic culture. It forms the backbone of the storyline in the Blood of Woden books.

"Strong runes he scored that night. Runes of hail, need and death."

Runes have long been linked to spellwork and sorcery. The clue is in the name itself: 'rune' comes from an Old English word meaning 'secret'. In a time when barely anyone could read, the power to transmit thoughts by scratching shapes onto wood must have seemed like magic in itself. Indeed, many of the earliest inscriptions comprise single words and rows of repeated letters that are better explained as curses and charms than as everyday writing. Even today, placing letters together to make a word is known as spelling.

At some point, each rune gained a meaning alongside its sound. From then on, a rune could stand for an idea on its own, which may explain the single runes found in so many inscriptions. How widely these meanings were understood, and to what extent they were shared across the Germanic world, is unknown. In the earliest times, the mere act of scoring runes was likely seen as magic. As writing began to spread, however, allotting meanings to the runes would have served to keep their magical uses distinct from their use in writing.

Almost everything we know about the meanings of the runes comes from three medieval poems, written in England, Norway and Iceland. The English poem is the eldest of these, being known from a tenth-century manuscript. Translations of this poem are widely available online. The names and meanings in the three poems concur to such a degree that it is generally agreed they must have come from a common original. All three contain direct references to heathen gods, including the only references to Ingui and Tiw found in any Old English source. The English poem cannot, therefore, have been composed later than the eighth century, as these gods would not have been mentioned so openly in Christian times. The Norwegian and Icelandic poems were written down in the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries respectively. Again, this is well into Christian times so the originals must be older.

There is no direct evidence of runes being used to tell fortunes in heathen times, but there are a number of references to 'tokens', 'chips' and 'lots' which were cast to the floor by those wishing to know the future. In some cases, these were said to have been marked with symbols, which many have taken to be runes. Even today, we use the word 'forecast' when attempting to predict the future.

Norse folklore has given the runes a heavenly origin. According to the poem, Runatal, the runes were discovered by Woden on his quest to learn the secrets of the world. He hung himself from a tree for nine nights without food or drink until strange shapes appeared before him. He then gathered these in and (presumably) took them back to Esyard. How he passed them to mankind is not recorded. This brief tale has been expanded to form the introductory chapter to The Runemaster. While there is no record of this story in any Old English poem, Woden is linked to runes and magic in other English sources, and there is nothing to suggest the English did not know this tale.

We shall never know for sure when runic magic died out, but among the English, it may well have outlasted the use of runes in writing.

The English Futhorc

The twenty-nine letters of the first English alphabet, or Futhorc, which helped inspire the hard-hitting action in The Runemaster.

The English Futhorc

The twenty-nine letters of the first English alphabet, or Futhorc, which helped inspire the hard-hitting action in The Runemaster.

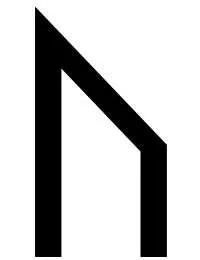

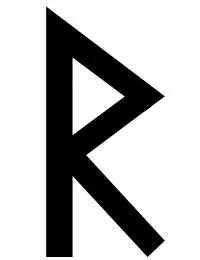

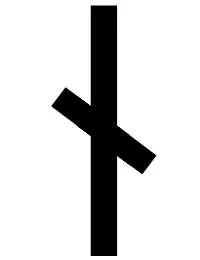

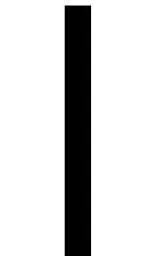

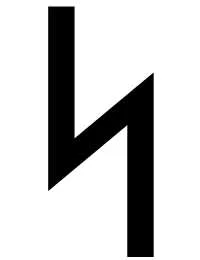

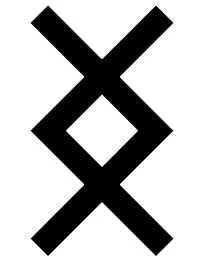

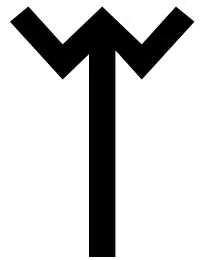

Shapes, sounds and meanings: rune by rune

These are the twenty-nine runes recorded in the tenth-century Old English Rune Poem. Additional runes are known from a few other manuscripts but they do not appear to have been in widespread use. For the purposes of the Blood of Woden books, the English Futhorc comprises the twenty-nine runes of the Poem.

Each rune had a name, a meaning and a sound. The names of the runes are in red, and are shown as they appear in the Poem. With the exception of the last three, the runes take their names from everyday Old English words. Where these have evolved into Modern English words, the modern form is shown in brackets to the right.

The meanings of the runes are very much open to interpretation. The descriptions show the most commonly accepted meanings, based upon the Old English Rune Poem and on the words used for the names themselves. In the text below, Old English words are shown in italics with their modern forms in quotes beside them.

The word feoh originally meant 'cattle'. In the days before coins came into use, cattle were often bartered for other goods. Because of this, feoh became a byword for 'payment', hence the modern word 'fee'.

This rune was replaced by the Roman letter F. In most positions, it was pronounced as a modern F, as in fether 'feather' or lyft 'lift'. Between vowels, however, it had the sound of a modern V, as in seofon 'seven'. The letter V was not used in Old English and did not become widespread until later in the Middle Ages. This rune is usually taken to mean wealth, worldly goods and the sharing of these.